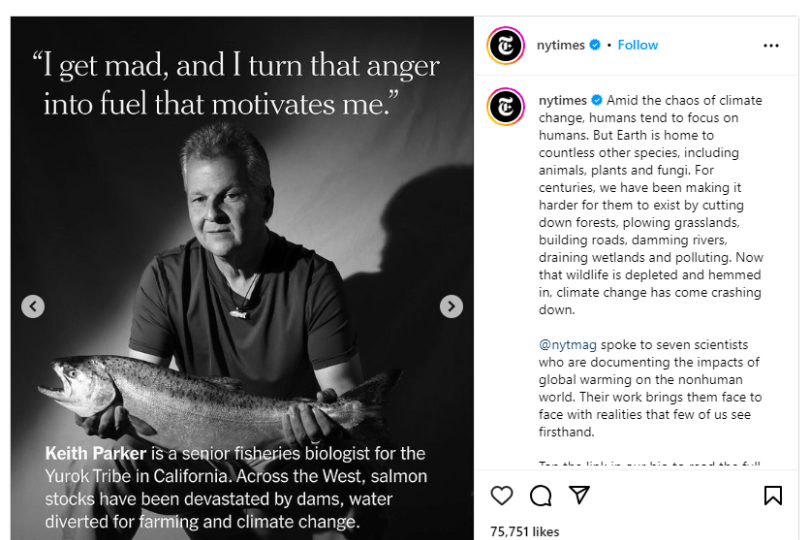

Parker in NYT Magazine: The Scientists Watching Their Life’s Work Disappear

Keith Parker was interviewed in the New York Times Magazine article The Scientists Watching Their Life’s Work Disappear about his work studying and protecting salmon in the Klamath River. The following is an excerpt from the full story, which features striking portraits and stories from multiple scientists.

Parker is a senior fisheries biologist for the Yurok Tribe in Northern California. Across the West, salmon stocks have been devastated by dams, water diverted for agriculture and climate change.

I grew up fishing on this river. I remember massive amounts of fish that used to come in, salmon in particular. It would be so noisy, you would actually hear it. They would leap into the air, splash and fin. Finning is when they break the surface with their dorsal fin. As they made their way upriver, it was amazing to see hundreds of salmon backs finning together.

We are known as salmon people, like all the tribes in the Klamath River Basin. Salmon and the Klamath River are the lifeblood of our culture and our community. Unfortunately, since the late ’90s, we’ve seen this gradual decline. The state and federal agencies closed the fishery this year, based on the low predicted returns. Our Yurok Tribal Council also closed our fishery for the year.

I think it was the right decision, but it’s devastating to our community to not be able to harvest salmon. I notice that when we have really good salmon runs, people are happy. And years like this, where we have a closed salmon fishery, we see increases in drinking, domestic violence and a lot of detrimental things.

The loss of the size of the run has hurt not only people, but Mother Earth. All those fish were breaking down and being absorbed into the forest. That’s how you get ocean nutrients in trees hundreds of miles upriver.

All the terrible things I’ve seen, all the detrimental changes to the environment, all the impacts of climate change — I use it to fuel my motivation to be a better scientist, to be a better human being, to be a better steward of the land. And honestly, part of it is anger. That’s fuel, OK? I get mad, and I turn that anger into fuel that motivates me.