Rodríguez-Cruz: Puerto Rican farmers will replant despite Ernesto’s impacts

Editor’s note: This story originally appeared on Yale Climate Connections, by Luis Alexis Rodríguez Cruz on August 27, 2024.

The well-known Puerto Rican song “Temporal,” or “Storm,” includes the line, “the green hurts in the eyes, the harvest that is lost.” The song captures how many of us felt upon seeing images of our farmers’ crops on the ground, the result of winds and rains from Tropical Storm Ernesto as it passed through the eastern part of Puerto Rico on August 14.

“Having to see years of work on the ground is something that stirs all your senses. Moreover, a lot of money is invested. I lose my appetite. It’s like mourning,” said Marisita López Cortés, a farmer from the mountainous town of Villalba, in the south of the main island of the Puerto Rican archipelago. Those words echo the sentiments of people in the region who saw their crops on the ground, people in whose eyes the green hurt. And a large part of that green was plantain and banana crops.

Damage at Finca Hacienda López Cortés in Villalba, Puerto Rico, after Tropical Storm Ernesto. (Photo credit: Marisita López Cortés courtesy of Luis Alexis Rodríguez Cruz.)

Heavy rain followed by landslides

According to the nonprofit organization Climate Central, the average ocean temperature along Ernesto’s path to Puerto Rico was 0.8°C higher than normal and between 80 and 100 times more likely due to climate change. We know that higher temperatures create stronger storms.

The Puerto Rico Department of Agriculture reported that the estimated amount of crops lost is now $23 million. Plantains, bananas, and coffee were the primary crops affected.

Reports, photos, and stories from various municipalities, from Santa Isabel in the south to Maunabo in the east, and Barranquitas and Corozal in the mountains, show farms overwhelmed by the gusts of the fifth storm of the 2024 hurricane season.

“We lost half of the plantains. Eight inches [of rain] fell. We have no access to the farm; landslides took over,” López Cortés said in Spanish.

According to the National Weather Service, the mountainous area of Puerto Rico recorded about 10 inches (25.4 centimeters) of rainfall and wind gusts of up to 86 mph (138 kph).

López Cortés had several crops interspersed throughout her farm, including plantains and coffee. This helped many of her crops withstand the strong winds. But torrential rain caused landslides that destroyed crops.

K. Stephen Hughes, who heads the Puerto Rico Landslide Mitigation Office, affiliated with the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, estimated that there were around a hundred landslides.

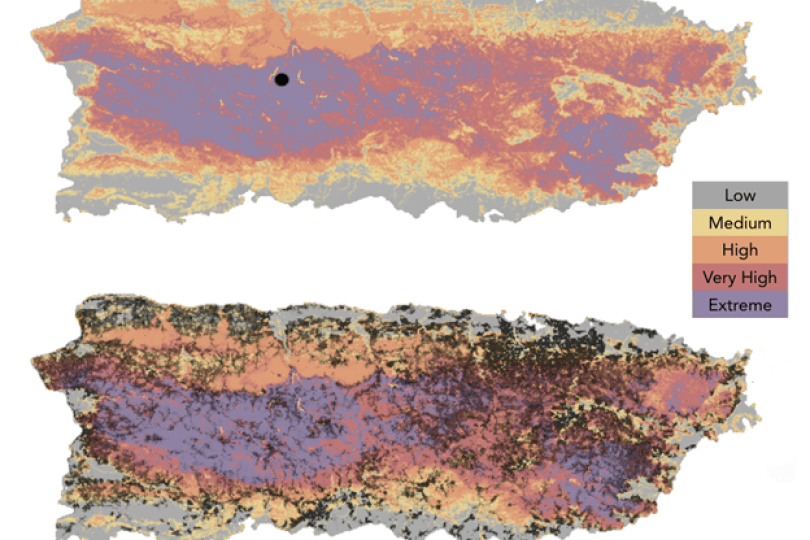

Populations susceptible to landslides in Puerto Rico (Image credit: Study Assessing Social Vulnerability to Landslides in Rural Puerto Rico (West et al., 2022)

A significant percentage of Puerto Rico is susceptible to landslides, and a large portion of agricultural production occurs in those areas.

“Almost all the [landslides] I’ve seen are shallow soil failures,” Hughes said. “Shallow does not mean they are less significant. They still block roads, isolating different communities.”

It’s important to note that the vulnerability to landslides is a stressor for people in that area, particularly for farmers who see their lands affected by them.

Government and grassroots help for farmers

The recovery work will be arduous. Farmer Stephanie Rodríguez discussed this problem with a farmer she called Junior from Ciales, a mountainous region in the middle of the main island. In a video she uploaded to Facebook, both said that they have seen an increase in extreme events, such as droughts and torrential rains.

This weather variability complicates farm planning. Part of the planning for many includes insuring crops through the Agricultural Insurance Corporation of the Puerto Rico Department of Agriculture.

But for several crops, these insurance policies only provide coverage when the event is classified as a hurricane — they do not include tropical storms.

“We are asking farmers to submit their loss reports … because we are designing a program to provide them with compensation [for their losses],” said Secretary González Beiró in an interview with Telemundo published August 15.

An option available for farmers is the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program administered by the Farm Service Agency of the Federal Department of Agriculture, in addition to other state and federal options.

López Cortés said she has already contacted service providers to work on the applications for these programs. But many people do not have the technical or administrative resources to participate in these programs.

After Hurricane Maria, bureaucracy and the slow restoration of local infrastructure prevented a timely recovery on farms. But various grassroots groups and organizations, including government agencies themselves, have established initiatives that help people apply for these programs.

What’s next?

What would agricultural and fisheries safeguard programs look like if they were adapted to the climate reality we are experiencing? How much would it help to have accessible services and programs for risk planning and mitigation in these sectors, which are so important to our food security?

Another line of the song that opened this column is, “What will become of Puerto Rico when the storm arrives?”

One answer to that question could be the one offered by Junior, the farmer Rodríguez interviewed: “We will keep planting.”

It’s a sentence that Marisita López Cortés supports and hopes will materialize on her farm.